By MEE staff

The Nakba (the Catastrophe) dismantled Palestine and Palestinian society 75 years ago through the destruction of 500 villages, the forced exile of half of the Palestinian population, the loss of prominent Palestinian industries, and the eradication of important social and cultural traditions that united Palestinians. In commemoration of the Nakba and the atrocities that followed, the act of preserving Palestinian collective history serves as a reminder of the innovation, prestige and resilience that helped shape the region and made it thrive despite British colonialism. Honouring the legacies of this history, this photo essay examines some of what was lost in Palestine, starting with orange groves. Bir Salem, located in the Ramle subdistrict, was one of many Palestinian villages that produced the famous Jaffa orange, developed by Palestinian farmers in the mid-19th century. Citrus manufacture in historic Palestine was one of the leading industries, with the Jaffa orange dominating global markets, making it the main export by 1900. By the 1930s, the citrus industry consisted of 77 percent of the total value of exports from Palestine. The image above depict orange groves in Bir Salem and the top image shows agricultural workers sorting through oranges in Jaffa in 1907. (Library of Congress and Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Throughout southern Palestine, orange groves decorated the countryside, with many Palestinian farming villages cultivating the crop. Yet this industry was demolished for Palestinians during the Nakba. Following the events of 1948, the fate of the Jaffa orange was placed at the centre of international dialogue. In 1949, during the Lausanne Conference, Palestinian refugees petitioned for the right to return to their orange orchards, and for the right to tend to their lands which had suffered without proper cultivation. Yet just a year later Israel would pass the 1950 Absentee Property Law, which allowed the state to confiscate all land and property belonging to Palestinian refugees. Many of the orange groves were destroyed, including the orange groves of Bir Salem. The village, once home to more than 400 Palestinian families and home to a vibrant orange grove, was turned into a kibbutz in June of 1948 and is now named Netzer Sereni. The image above depicts the Holocaust memorial statue in Netzer Sereni (Wikimedia/Avishai Teicher)

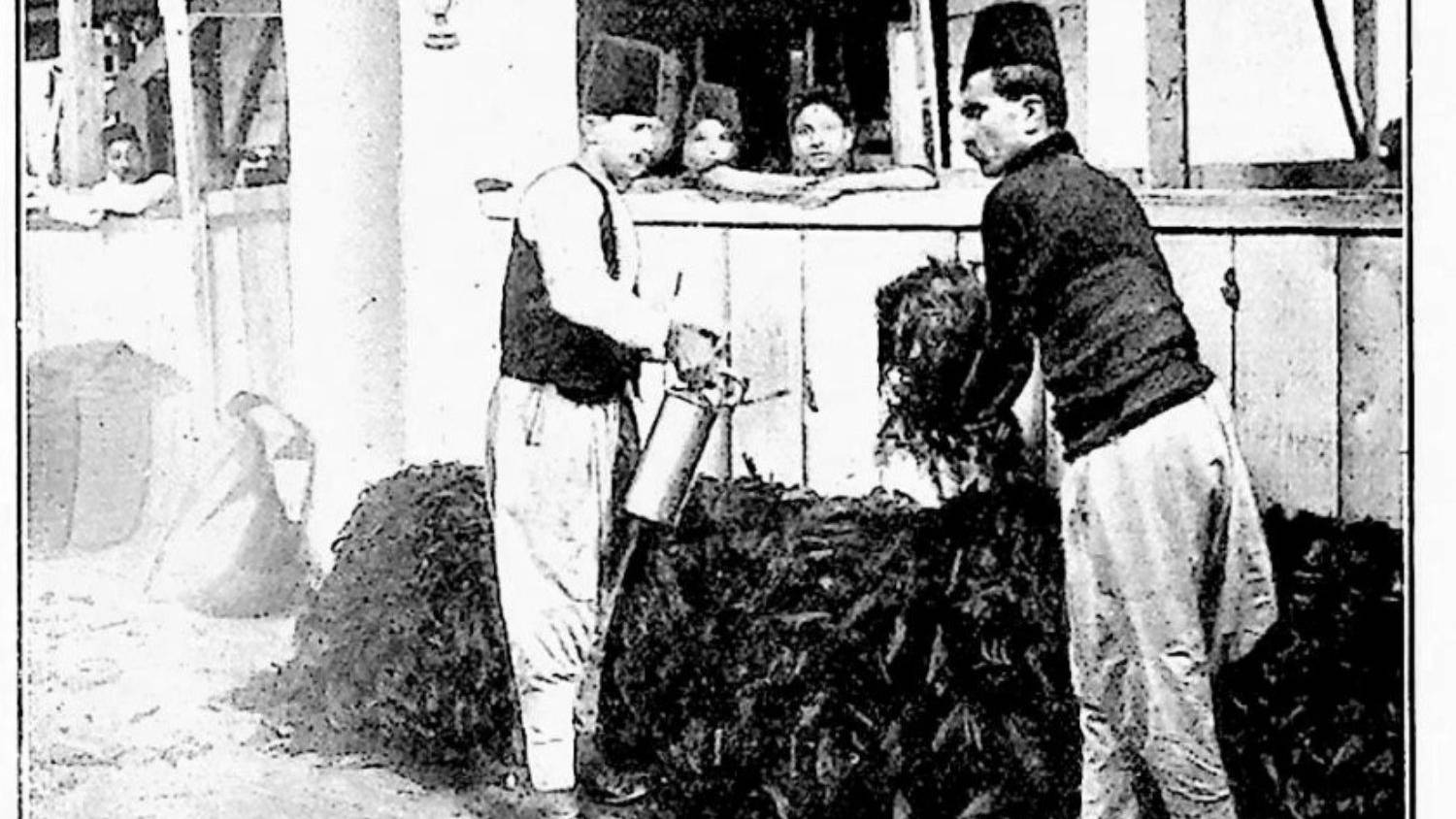

During the 1920s, Haifa was the administrative capital of Palestine and was a place where new industries began to flourish. One important area of manufacture was tobacco farming and production, which was taken up extensively by Palestinian farmers in the early years of the British mandate. One of the first and largest factories in Palestine was the Karaman, Dick & Salti Cigarette Company. (Industrial Palestine, 1925)

The company was founded by notable urban elites like Hajj Tahir Karaman, one of Palestine's most esteemed entrepreneurs and a key figure in the development of Palestinian national industries and urban development in Haifa. Palestinians were encouraged to support “watani” national industries, such as Karaman, Dick & Salti Cigarette Company, to promote and strengthen indigenous enterprises. Karaman was also a leading political figure in historic Palestine as the founder of the Palestine Arab Party and a member of the Haifa Chamber of Commerce, as well as a member of the National Committee which headed the general strike in Palestine during the Great Revolt. The photo above depicts Haifa in 1898. (Wikimedia)

The Karaman, Dick & Salti Cigarette Company was destroyed during the Nakba. The cigarette factory remains in Haifa as an abandoned rustic property, robbed of its historical might. The picture above shows women working in a cigarette factory in Nazareth in the late 1930s or early 1940s. (Israeli State Archive)

One of many historic towns in Palestine is Qisarya, an ancient fishing village once the capital of Palestine Primea and Syria Palaestina during the Byzantine and Roman eras, respectively. Qisarya, an Arabised version of the name Caesarea, served as a major intellectual hub of the Mediterranean. The ancient city has thousands of years of recorded history from the time of Herod I to the Mamluk conquest in 1265. The photo above depicts Qisarya in 1938. (Library of Congress)

In more recent history, Qisarya became a village of immigrants from all over the Muslim world during the rule of the Ottoman Empire. In 1880, following the Austria-Hungary occupation of Bosnia, Caesarea was allotted to Bosniak Muslims fleeing persecution. The Bosniak community reestablished the village amid the ancient ruins and lived there until 1947 when they were forced out by Zionist militias. The photo above depicts what remains of the Bosniak mosque there. (Wikimedia)

One of the greatest annual events to take place in Palestine was the Nabi Rubin festival, which took place in the historic village of Nabi Rubin in the Ramla subdistrict. Every year, between July and September, tens of thousands of Palestinians from the surrounding villages of Yaffa, Ramle and Lydd made their way to the shrine of the Prophet Jacob's son Rubin, and held a month-long festival in his honour. During this month-long festival, tents would surround the shrine and the nearby villages to accommodate the pilgrims. Various marketplaces, restaurants and coffee stands were also set up for the pilgrims during the celebration. There were a series of religious ceremonies put together by dervishes as well as non-religious activities like dancing, fortune telling and storytelling. The photo above depicts the Nabi Rubin festival at some point between 1920 and 1933. (Library of Congress)

In 1935, the first-ever film was showcased at the Nabi Rubin Festival. So important was this festival that urban city folk and peasants alike made their way there annually. It became one of Palestine's most prized religious and cultural events, and every year it brought united Palestinians in celebration. The picture above depicts the festival in 1930. (Library of Congress)

The last Nabi Rubin Festival took place in 1946. In 1948, the village of Nabi Rubin and its surrounding lands were captured by Haganah forces and were confiscated, marking an end to the festival and this sacred tradition that had connected Palestinians with one another for centuries. Today, the Israeli moshav (settlement) of Gan Soreq sits just West of the Nabi Rubin Shrine. The picture above depicts the Nabi Rubin shrine in 2021.

Source: ME