By: Ibrahim al-Marashi , MIDDLE EAST EYE

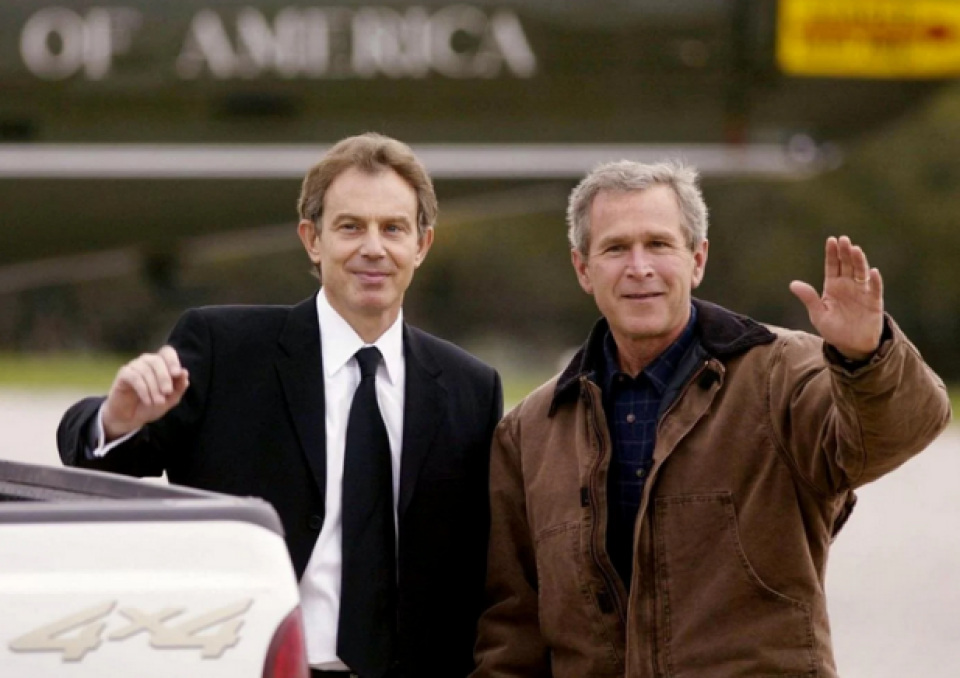

Portions of my work were plagiarised in the infamous 'intelligence dossier' that presaged the disastrous 2003 invasion - its roots can be traced back to a meeting in Texas a year earlier Last week, Middle East Eye published a secret memo about an April 2002 meeting between former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and former US President George W Bush in Crawford, Texas.

What is revealing about the memo is how determined both leaders were to invade Iraq at that point, abandoning all pretences at seeking a diplomatic solution. They also acknowledged how important it was to win over public opinion for an invasion.

It was a meeting in which Iraq’s fate was sealed. It was also a meeting that would propel me to infamy in February 2003. From Texas, a series of events transpired that landed me in the British parliament in June 2003, where I testified against Blair and this very campaign.

Even nearly two decades after the Iraq War was launched, this memo is revelatory. The role of the media was crucial for the US government and American domestic opinion during the Vietnam War, the 1991 Gulf War, and the conflicts in Somalia and Bosnia in the 90s.

This memo acknowledges the importance of the media battle. Yet, by the 21st century, the arena had evolved. The political theatre, managed by both the US and UK, involved global public opinion, 24-hour news cycles, the internet, Al Jazeera, the UN, and me, an Oxford student whose doctoral research was plagiarised in the rush to go to war.

'The PR aspect'

David Manning, then Blair’s chief foreign policy adviser, accompanied the British leader to the US president’s ranch in Crawford in 2002 and wrote up a memo of what transpired. While the two heads of state appeared to have made up their minds to wage war on Iraq close to a year before the 2003 invasion, the rationale was not explicit. The memo makes no mention of securing oil, establishing a democratic Iraq, or using the invasion as a means to end terrorism.

They did not even broach top-secret military strategy. A small group within US Central Command had been secretly exploring options for invading Iraq.

While the decision to go to war had been made before the military aspects were planned, the media battleground had to be handled. “Bush accepted we needed to manage the PR aspect of all this with great care,” the memo stated, adding that both leaders agreed the public relations strategy must highlight “the risks of Saddam’s WMD [weapons of mass destruction] programme and his appalling human rights record”.

The Blair government ultimately released a pair of “intelligence dossiers” to this end, aiming to sway public opinion, both domestic and international, and the UK parliament’s vote for war. The first was released in September 2002, focusing on Iraq’s alleged WMD programme.

![In that April 2002 meeting, Blair had expected Saddam to stymie the efforts of UN weapons inspectors who would be dispatched months later. Inspections were more spectacle than genuine disarmament: “If, as [Blair] expected, Saddam failed to [cooperate], the Europeans would find it very much harder to resist the logic that we must take action to deal with an evil regime that threatens us with its WMD programme,” the memo noted.](https://thatsenough.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/opinion-10-1024x1024.jpg)

In that April 2002 meeting, Blair had expected Saddam to stymie the efforts of UN weapons inspectors who would be dispatched months later. Inspections were more spectacle than genuine disarmament: “If, as [Blair] expected, Saddam failed to [cooperate], the Europeans would find it very much harder to resist the logic that we must take action to deal with an evil regime that threatens us with its WMD programme,” the memo noted.

The threatening nature of Iraq’s WMD programme was exaggerated in the September 2002 dossier, which claimed that such munitions could be prepared and launched in 45 minutes against British interests. This claim would generate significant controversy in July 2003, claiming the life of a government scientist, David Kelly, who was engulfed in a media storm and eventually found dead in an apparent suicide.

Architects of war

The second dossier focused on the myriad of secret police and spy agencies that violated the human rights of Iraqis and took part in WMD concealment. Blair had given that dossier to then-US Secretary of State Colin Powell in January 2003, and Powell referenced it during his February 2003 presentation to the UN on Iraq’s alleged WMD programme.

The issuance of these dossiers and the British and American attempts to sway the UN can be traced back to the Crawford meeting. The memo states, referring to the PR campaign: “The PM said this approach would be important in managing European public opinion and in helping the President construct an international coalition.”

The dossiers were not secret, but were meant to be UK “intelligence reports” released to media organisations and the public. The UN was key to the goal to “construct an international coalition”.

Following Powell’s presentation, Jon Snow of Channel 4 News revealed that whole sections of the 2003 dossier were copied off the internet by the British government from an online article I published, based on my Oxford PhD - including my grammatical mistakes. Today, the memo from 2002 has provided me with a glimpse of how these events unfolded.

When Channel 4 released the plagiarism story, it was assumed that UK intelligence services, such as MI6, had produced the dossier. In fact, it was produced under the aegis of Blair’s then-communications director, Alastair Campbell.

The memo’s emphasis on the need to win over the media and public opinion explains why Campbell’s office was involved. This unit in the Blair administration had crafted and molded “intelligence”, and during the rush of meeting the 24-hour news cycle, mistakes were made.

The memo released by MEE underscores that the case for war was not based on an unaltered intelligence analysis, which mistakenly assessed that Iraq had WMDs. From the onset of the Crawford meeting, the architects of the war had planned for a media campaign devoted to the appearance of WMDs in Iraq to legitimise an invasion. If intelligence or UN inspections would later support their claim, all the better. Regardless, the determination to go to war had been decided in Texas.