by : Fiona Harrigan , reason

Today's journalists aren't speaking truth to power by not-so-subtly agitating for direct military involvement in Ukraine.

On this day in 2003, the United States launched its air invasion of Iraq, with the ground component beginning one day later. It was the first stage of a war that would ultimately drag on for over eight years, killing thousands of American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians as the U.S. and its allies sought to overthrow Saddam Hussein's government.

Nineteen years on, Americans watch as a conflict embroils Eastern Europe. Russian President Vladimir Putin's large-scale invasion of Ukraine beginning last month has brought frequent reports of deaths of innocents and strikes on civilian spaces.

Horrific scenes from the conflict in Ukraine have fetched headlines much like those published during the Iraq War. But there is a difference between journalistic reporting on a conflict and coverage that trends more toward activism. Reporters operating under the guise of objectivity repeatedly trended toward the latter approach during the Iraq War. Now, as establishment journalists not-so-subtly agitate for a more interventionist U.S. policy in Ukraine, it's worth keeping an eye on these tried-and-trued hawkish tendencies.

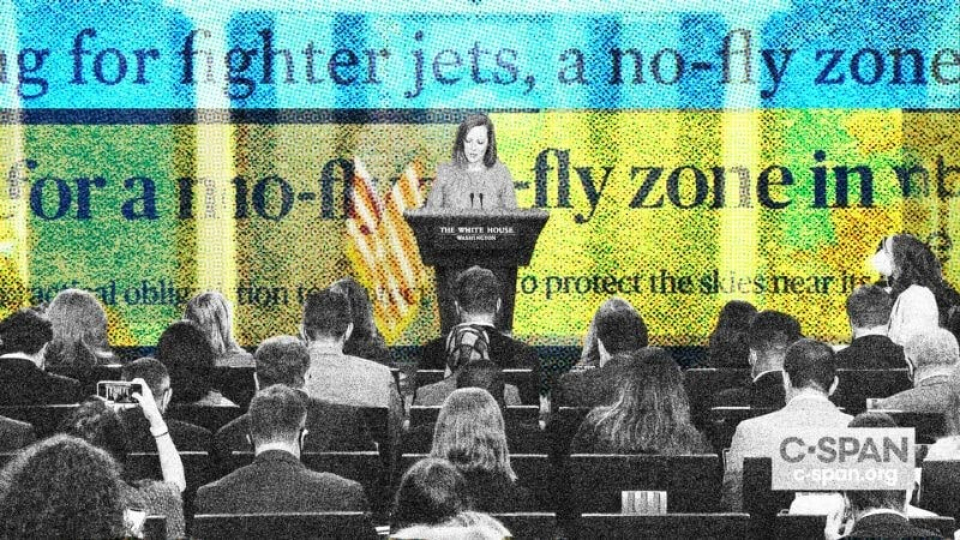

In a press conference on March 15, reporters pelted White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki with questions regarding the Biden administration's opposition to certain military support for Ukraine. There were over one dozen questions mentioning military assistance—including five distinct mentions of a no-fly zone—and only one question about the potential American role in facilitating negotiations between Russia and Ukraine.

Neither were the numerous questions about military assistance purely fact-based. "Zelenskyy and other Ukrainian officials have made so clear that what they believe they need the most is more warplanes and fighter jets. So why is the U.S. assessing something different?" asked a reporter. "Why does the U.S. believe they know better what Ukraine needs than what Ukrainian officials are saying they need the most?"

Indeed, in old-guard media outlets and press conferences alike, journalists have taken a hawkish turn. Substack columnist Adam Johnson put out an article this week titled "Attacking Democrats From the Right: The Faux Adversarial Sweet Spot for U.S. Journalists," having compiled numerous recent examples of the conflict-hungry press. Among them: Richard Engel of NBC News calling the Afghanistan withdrawal the "worst capitulation of Western values in our lifetimes"; CNN's Jim Sciutto asking a State Department spokesperson why the U.S. wouldn't "shoot down the [Russian] planes that are bombing hospitals"; The New York Times' Peter Baker including a comment from a Raytheon board member as an example of someone opposing the Afghanistan withdrawal and later lamenting that "Biden saw no middle ground in Afghanistan between ending the war or endless escalation."

These instincts inevitably tinge mainstream coverage of conflicts, the public sentiment it provokes, and the questions lobbed toward press officials in the highest political settings, as this week's Ukraine briefing shows. "It's a time for tough questions, Peabody-baiting TV coverage, mugging about innocent life, and the need to 'act' 'now' to 'protect civilians,'" writes Johnson, "all of which just so happens to track with the forces of increased militarism."

The hawkish press played a significant role in shaping public opinion during the Iraq War, with reporters helping to bolster government justifications for the war. Alternative views were few and far between. The common criticism of the Iraq-era press was that "it had been too slow to subject government claims to scrutiny—indeed, that it had amplified official assessments in advance of the war and given them credibility," as The Atlantic's Cullen Murphy wrote in 2018. The New York Times' Judith Miller and other reporters at establishment outlets propagated false information about Saddam Hussein's regime, including charges that it possessed weapons of mass destruction. (Miller, for her part, later released a book defending the mistakes she made in her coverage—"not because I lacked skepticism or because senior officials spoon-fed me a line.")

The Iraq War was clearly a different conflict than the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the U.S. plays a different role now than it did then. The U.S. is not directly involved in the fighting in Ukraine, and there are no American boots on the ground as there were in Iraq. Much of the Iraq era's reportage centered on a politically and publicly sanctioned conflict. In a sense, this makes an activist press uniquely concerning during the current conflict. Broadly speaking, contemporary journalists have aligned their questioning with a path of increased militarism that the American public does not desire when it comes to Ukraine.

Sitting in "the faux adversarial sweet spot," members of the establishment press are pushing back on what the American public has in large part rebuffed. When a CBS News/YouGov poll asked respondents what they thought of a no-fly zone "if it's viewed as an act of war"—which it necessarily would be in the Ukraine-Russia conflict—62 percent opposed it. The Biden administration has ruled it out as a component of the American response, with good reason.

The American press isn't speaking truth to power by pushing in less-than-objective ways the matter of direct military involvement in Ukraine—an idea that both the power and the people it rules have rejected. Nor is it playing an informative role by asking after the same war-related information on a self-admitted "168th" occasion.

Establishment media outlets and the journalists who write for them are by no means chiefly responsible for the disastrous Iraq War. Governments, not journalists, wage war. But they absolutely deserve a heap of the blame for uncritically perpetuating half-truths and government accounts when balanced coverage may have made restraint a more publicly desirable approach. Now playing a hawkish role in America's response to the conflict in Ukraine, they're displaying a concerning behavior in full view: In the name of balanced national security coverage, they're mercilessly hounding officials who dare to convey the dangers of intervention.