By Kendrick Lu

Bernie Sanders has introduced a new resolution to cut off US support for the horrific Saudi-led war in Yemen. The measure is a crucial step toward peace — but it will have to be backed up with serious pressure on Joe Biden, so he doesn’t flout the resolution.

In the two months since a United Nations–brokered ceasefire expired in Yemen, a tenuous peace has held. Yet with every passing day, that peace looks more and more precarious. The Saudi-backed Yemeni government has sanctioned companies that import fuel to areas held by the Houthis, a fundamentalist movement fighting the government, and the Houthis are targeting terminals in southern Yemen with drone strikes to deter tankers from loading crude oil. Both worsen a humanitarian crisis that has long been called the worst in the world. Nor is there anything preventing the Saudis from resuming their own airstrikes, grounding all flights, or retightening the blockade.

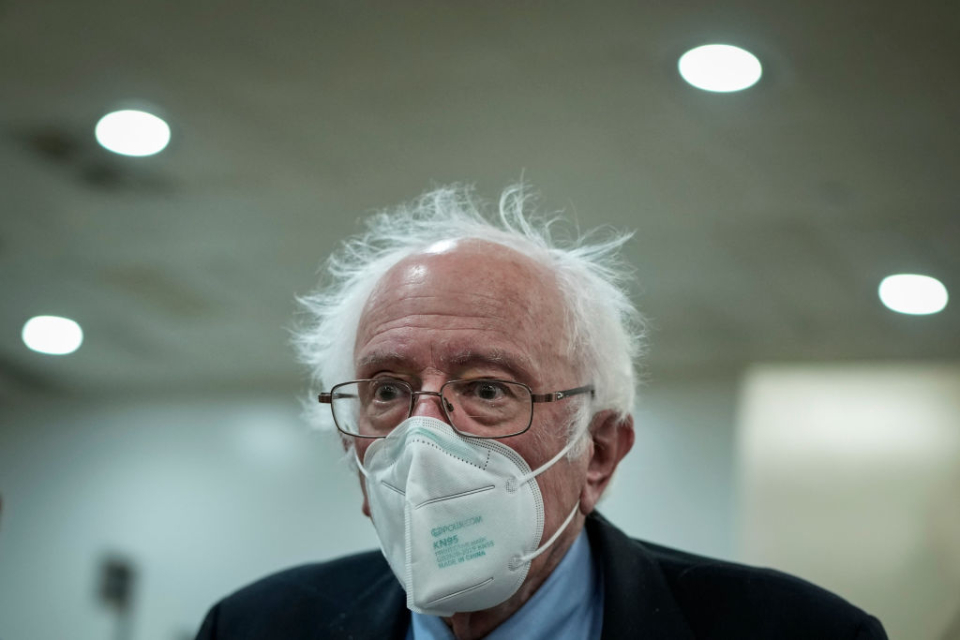

Senator Bernie Sanders’s new Yemen war powers resolution aims to strengthen that tenuous peace by blocking US backing for the Saudi-led war. Earlier this week Sanders announced he has the requisite support to pass a resolution, and that he could bring it to the Senate floor for a vote as early as next week. If approved and signed into law, the resolution would require President Joe Biden to withdraw several forms of military support for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.

Sanders’s resolution is certainly a positive development. It would force the Saudi-led coalition to think twice before resuming the war and, at least in theory, withdraw US collaboration in an immoral war that has killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and pushed millions more into near-starvation.

Unfortunately, based on previous presidents’ record of skirting war powers resolutions, the Biden administration may not heed a congressional entreaty to drop military support for Saudi Arabia. Foreign policy progressives will have to keep up the pressure even if Sanders’s resolution passes — and then initiate a broader fight against the executive branch’s unchecked war-making powers.

The United States, Yemen, and the War Powers Resolution

Sanders’s Yemen war powers resolution draws its lineage to the 1973 War Powers Resolution (WPR), a Vietnam-era statute designed to dial back Richard Nixon’s bombing of Southeast Asia. While the US Constitution grants Congress the exclusive power to declare war — and most constitutional scholars interpret that prerogative as including the ability to initiate war through the deployment of military force — US presidents quickly developed a habit of forgoing congressional declarations of war before sending troops into combat.

The 1973 WPR was an effort to wrest the war-making power away from the president and restore it to Congress. In a nutshell, the act requires the president — if using military forces to engage “in hostilities or situations where hostilities are imminent,” among other circumstances — to inform Congress within forty-eight hours. The president then has sixty to ninety days to recall the engaged troops unless Congress authorizes the use of military force.

Sanders’s resolution builds on this restraining mechanism. It rehearses the president’s unmet obligations under the 1973 WPR, noting that the president has introduced military forces into the Yemen conflict; that the conflict meets the definition of “hostilities” under the 1973 law; that Congress has not permitted the president to continue engaging in hostilities; and therefore, that the president must remove US armed forces from hostilities no later than thirty days after the adoption of the measure.

If approved, the resolution would bolster the fragile peace that has survived in Yemen for the past few months. A strong vote in the Senate would signal to Riyadh that continued US military support is on the ropes; that reigniting the war would mean going it alone; and that returning to the UN bargaining table is the most sensible path forward.

What is less clear is how much the resolution would limit US military support for the Saudis. The current language is encouraging, mandating Biden to pull US armed forces from “hostilities” in Yemen. Concise yet capacious, the measure provides two definitions of “hostilities”:

- “Sharing intelligence for the purpose of enabling offensive coalition strikes; and providing logistical support for such strikes, including by providing maintenance or transferring spare parts to coalition warplanes engaged in anti-Houthi bombings in Yemen,” and

- “The assignment of United States Armed Forces to command, coordinate, participate in the movement of, or accompany the regular or irregular military forces of the Saudi-led coalition forces in hostilities against the Houthis in Yemen.”

This language casts a wider net than Sanders’s previous Yemen resolution, which defined “hostilities” only as “including in-flight refueling of non-United States aircraft conducting missions as part of the ongoing civil war in Yemen.” The current resolution also provides the starker limitations that were missing when Biden announced in February 2021 that he would be ceasing all “offensive” support for Saudi Arabia’s coalition.

But another question looms as the Senate prepares to vote on the resolution: If it passes the Senate and avoids the president’s veto, will Joe Biden actually to observe its requirements? The executive branch has played fast and loose with the War Powers Act since its 1973 passage, and as a result, the act hasn’t had the restraining effect on the “imperial presidency” that Congress intended.

Presidents from both parties have instead twisted themselves into legalistic pretzels proving their compliance with the WPR. One move has been to exploit the definition of “hostilities,” which the 1973 act failed to define. In defending its drone missile strikes in Libya in 2011, the Obama administration claimed that the attacks didn’t amount to “hostilities” because US troops suffered no danger of return fire or casualties, and because no ground troops were involved. Donald Trump’s Department of Defense lawyers justified US involvement in Yemen on similar grounds in 2018, insisting that “hostilities” only meant “a situation in which units of US armed forces are actively engaged in exchanges of fire with opposing units of hostile forces” — insulating from scrutiny the deadly support US forces were providing. (This recent history is a large part of why the Yemen resolution’s explicit definition of “hostilities” is key.)

Other arguments have bordered on the absurd. When bombing Kosovo, Bill Clinton’s Office of Legal Counsel argued that Congress had authorized him to continue hostilities beyond sixty days because it had passed an appropriations bill for military funding — even though the 1973 WPR explicitly prohibits using an appropriations bill for inferring congressional authorization.

If the Biden administration truly wants to continue its military support for the Saudi-led coalition, it will probably concoct an equally absurd legal argument resolution to do so.

Attacking the Imperial Presidency

Whether Biden chooses to abide by the resolution’s terms or flout them will probably depend on the broader US-Saudi relationship — which has shifted in the Saudis’ favor lately.

Biden has hardly made Riyadh the “pariah” that he promised on the campaign trail; just this week, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit against Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for his role in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, following a recommendation from Biden’s Department of Justice that he receive head-of-state immunity. The anger in the fall over OPEC+’s oil cuts has now subsided. And Xi Jinping’s visit this week to Saudi Arabia likely reminds the Biden administration that the Saudis can pick and choose powerful allies in an increasingly multipolar world. Against that backdrop, Biden might be reluctant to drop military support for Riyadh.

Nevertheless, passing Sanders’s resolution — and pressuring Biden not to weasel out — is a vital step toward peace in Yemen. If Biden concedes, it would be a tremendous victory for ordinary Yemenis. And then perhaps progressives could turn to bludgeoning a key pillar of the US empire-making project: the president’s near-unilateral ability to make war.

Source: Jacobin